This is why they called him Magic

Ask me the best hockey player I ever played with and I should probably name someone other than Michael Holmes.

For a few years in the mid-2000s, for instance, Valeri Kamensky was a regular at our late-night pick-up skates at Rye Country Day. At the time, Kamensky was around 40, and not far removed from a career in which he won an Olympic gold medal with the old Soviet Union, a Stanley Cup with the Colorado Avalanche, and was inducted into the International Hockey Hall of Fame. The story goes that when the NHL put together a team for a mid-season series against the Soviets called “Rendezvous ‘87”, the young Kamensky was the player who gave Gretzky and Lemieux fits.

Valeri Kamensky was that good. And yet when he was on the ice with Michael Holmes, it wasn’t entirely clear who was better.

Michael’s official hockey resume wasn’t the story. He led Rye High School to the state final in 1982. Then Northwood and Elmira College. Then a few years of minor league and pro leagues overseas. In Rye, others had more impressive careers, some of them his own brothers. But even when those players returned to town, Michael had a way of standing out.

For many of us, he was the best hockey player we knew, and possibly the best we ever saw in the category our friend Dennis Megley called “age 25 through the rest of your life.”

Well into his 50s, Michael didn’t skate as much as he floated on the ice. He would carry the puck through the neutral zone, appear to be looking in one direction, then saucer the puck over two sticks and onto your tape in front of a half-open net. His nickname was Magic for a reason. One of Michael’s teammates at Northwood Prep, Tony Granato, went on to be an NHL All-Star and played on a line with Wayne Gretzky in L.A. “If I had Michael’s hands,” he once said to Michael’s former Rye teammate Jay Altmeyer, “I’d be Gretzky.”

One season when my old high school teammate Lowell and I were roommates we staged a scoring competition between us for late-night games, which was equal parts pathetic and inconclusive: When one of us ended up on a line with Michael, it wasn’t even fair.

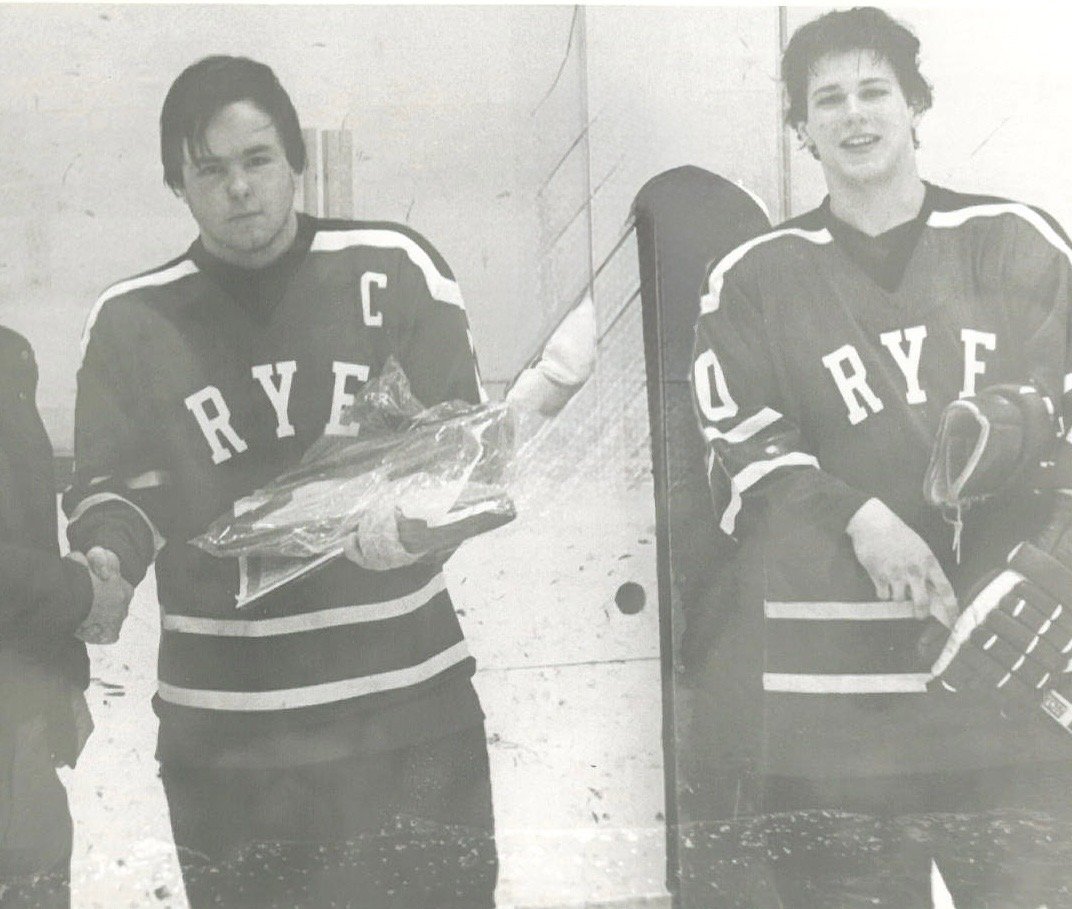

Michael Holmes, right, and Jay Altmeyer

I loved playing with Michael, but it was an adjustment. No one made the game easier. When you scored a goal with Michael on your line, of course you scored. When you didn’t, you had no excuse. Great hockey players love to show you how good they are. Michael enjoyed showing you how good you could be, too.

Somewhere in there is probably an explanation for why he didn’t progress further as a pro. It wasn’t a lack of ability. But hockey at the elite level is a grind, and Michael still viewed it as if it should always be fun. He loved to show up at the rink when everyone was already on the ice and compete as if these were the only games in the world that mattered. When his team would score its fifth goal of the game for the win, starting a new game, Michael relished shouting across the rink for everyone to hear, “Nothing-Nothing!”

The only time I remember crossing him was a game when Michael was on the other team. As you can imagine, he was impossible to play against, darting in and out of reach when he had the puck, hunting you down and stealing it back when he didn’t. One night in the corner with the puck, Michael turned away from me, and I tried to lift up his stick. But I missed his stick and sent my blade straight into his mouth. Blood, teeth, the whole thing. It was a mess, and entirely my fault. Michael drove to the ER and, out of guilt, I followed him. When he emerged with a mouth full of stitches, I apologized and he accepted, but it wasn’t over. Back on the ice a week later I was carrying the puck into the zone and Michael drilled me into the boards with a laugh. Now we were good. That was the end of it.

I can’t say he and I were good friends. Even when my sister married his brother, or when his son Rob became one of my son’s favorite coaches, I’m not sure we talked about either at length. Michael was always easy to be around because he had zero ego, and I could see first-hand how much he prized and loved his family. Some of my favorite memories of him were the skates when he brought his daughter, Steph, to play, the two passing the puck between them as if on a string.

But plenty of people knew him better than I did. What I knew about Michael was mostly through the window of the game we both loved. It wasn’t just how he was better than the rest of us. It was how he radiated joy and generosity, and played as if a small part of us never has to grow old.

The 1980-81 Rye High School team Michael Holmes (20) is back row in the middle. My brother Josh is back row right next to coach John Zegras. My brother-in-law Billy Holmes (12) is front row middle, and Vinny Holmes is back left.