The difference between losing gracefully and losing well

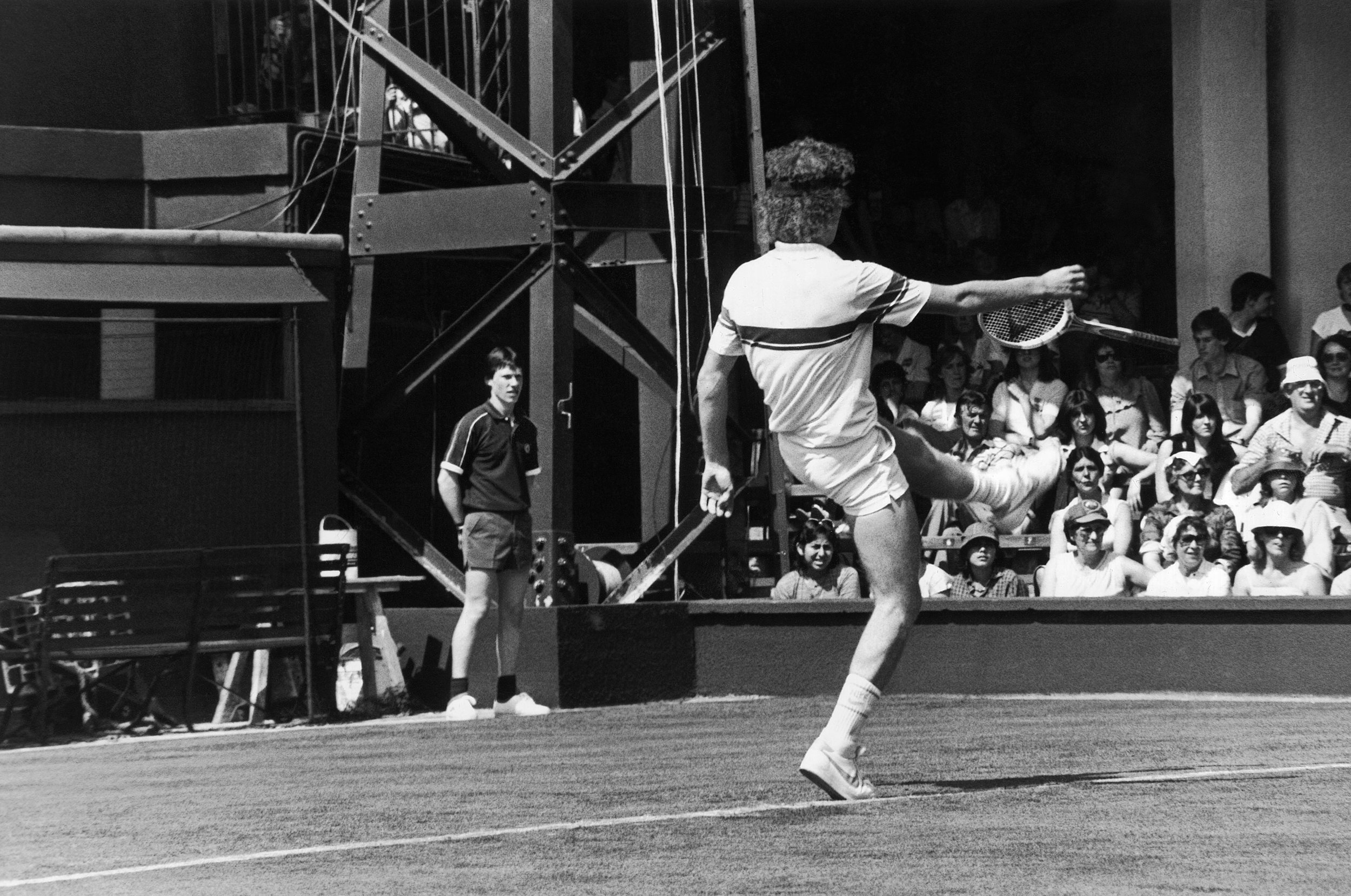

This was about an hour later, my clothes crusted with sweat, my cheeks still red. I was seated on the floor of our bedroom, and I was recounting to my wife my antics from that morning. Even by my pathetic standards, it was a doozy: I had smacked at least two balls into the net out of frustration; slammed down my tennis racket down so hard I cracked the frame; then, after missing a simple forehand wide, I exploded.

“WHY???!!!” I screamed. “WHY WOULD YOU DO THAT??!!”

To answer your next questions, yes, I got plenty of stares from the other courts. But, no, thankfully, my kids weren't around to see it.

“Don’t worry,” Lisa tried to console me. “You’re not the first person to act like that on the tennis court.”

“No,” I said. “But did any of those people just write a book about the value of losing?”

Lisa had no counter. She knew I was right.

In fairness, I was candid about my failings as a loser right at the start of Win at Losing. I tell the story about my son’s meltdown on the tennis court, and how Lisa sensed it could all be traced to me. I was the right person to chronicle the effects of losing simply because it had long been such a personal minefield. At no point did I vow to stop throwing sporting goods.

As I wrote, “My authority in writing this book does not stem from the graceful and admirable ways I’ve lost in my life but rather the opposite.”

Still, this was all written at the outset of this multi-year long exploration into the benefits of losing, in which I ultimately concluded these setbacks should be embraced as essential ingredients for growth. You spend enough time immersing yourself in concepts like growth mindsets and counterfactual thinking, you think you'd at least be able to avoid acting like a jackass in an inconsequential club tennis tournament. I mean, I talked about this stuff on the TODAY Show! Yet there was my Babolat racket, battered and mangled on the ground, wholly unimpressed.

So how is it that someone who espouses the importance of embracing failure can handle failure in such comically poor fashion? Is this what hypocrisy looks like?

Sort of.

But not really.

Look, I would love it if l lost tennis matches, shrugged my shoulders, then patted my opponent on the back. (Actually I would love it even more if I won. Winning would be great, too.) I have neither the time nor the disposable income to be smashing $200 rackets at will, and I am horrified by the thought of my sons following suit. (“I would kill Charlie if he did that,” Lisa said -- which is not true, because I would kill him first.)

But there is an important distinction between losing gracefully and losing well, and while I think we can all agree I fell woefully short of the former, the latter is where I choose to spend most of my energy. It has less to do with decorum, and more to do with what we extract from these episodes well after we've picked up our tortured equipment and gone home. Losing gracefully requires self control, but losing well is about self awareness. Losing well is in the painful unpacking of a defeat in the hopes of understanding why. It doesn't preclude you from frustration or the temporary loss of perspective. There is still a strong likelihood that you will resemble a second grader beaten out for the last cupcake.

But far more valuable is the ability to harness that energy into something worthwhile: a shift in strategy, greater humility, renewed motivation. There's a new Gatorade commercial out recently that captures this dynamic perfectly, with everyone from Michael Jordan (cut from his high school varsity) Eli Manning (a one-time league leader in interceptions), even Matt Ryan (the guy on the wrong end of the biggest comeback in Super Bowl history) endorsing the concept of “Making defeat your fuel.”

It's safe to assume all of these athletes had their petulant moments in the immediate face of disappointment -- ripped chin straps, kicked-over chairs -- each stemming from events of greater consequence than my little tennis match. At the U.S. Open I talked to the rookie Jon Rahm fresh off his own televised tantrum in the second round, when he repeatedly tore into the turf with his sand wedge after a bad shot. Later he said he knew he needed to control his emotions better, but that these outbursts helped him release his frustration in manageable increments rather than having it fester like soda shaken in a can. What’s interesting is that Rahm came back weeks later to win the Irish Open, which suggests if he didn’t lose particularly gracefully, he seemed to lose quite well.

The point is as much as we all regret losing our cool when cuffed around a bit, the real shame is when we fail to learn from it. It's embarrassing to explain to my boys why my tennis racket is broken beyond recognition. But I'd be even more embarrassed if the story of that match ended there.